Emergency Resuscitative Thoracotomy

Case

You are working in an ED with a trauma surgeon when you get the call: “28 year old male single stab wound to the chest, BP 98/57, HR 107, 99% O2, ETA 5 minutes.” You quickly gown up, and with the help of your nurses and techs, you set up the room for the incoming patient. You hear sirens as the medics pull into the ambulance bay and, much to your surprise, they are doing CPR. “Doc, he was totally with it, and then arrested a few moments ago! He was PEA on the monitor.” As the medics are transferring the patient to the gurney, you ask yourself, “Does this patient need a thoracotomy?”

Clinical Question

What are the indications, contraindications, and the steps to perform an emergency resuscitative thoracotomy (RT)?

Background & Guidelines

The emergency resuscitative thoracotomy, sometimes referred to as an ED thoracotomy, is often described as a last-ditch “damage control measure" when resuscitating a patient in traumatic arrest or impending traumatic arrest. Studies suggest that outcomes after resuscitative thoracotomy are generally poor. Survival rates have been reported between 9-12% for penetrating thoracic trauma. Outcomes after blunt trauma are even worse, with survival rates estimated between 1-2% [1].

Unfortunately, the Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) algorithm is not designed for patients with traumatic arrest. ACLS is intended for the patient with cardiac arrest from medical causes, as well as life-threatening primary cardiac conditions. In the medical arrest, chest compressions continue to circulate blood to the coronary arteries and brain temporarily while the underlying cause of arrest is diagnosed and treated. If the pump (the heart) is broke, we can take over for the pump via chest compressions as a temporizing measure.

Alternatively, traumatic arrest is almost never a primary pump (cardiac) failure. The leading cause for cardiac arrest in the trauma patient is hypovolemic shock in the form of hemorrhage. If the tank is empty and there is no volume to push through the pump, then pushing on an empty pump via chest compressions will yield very limited benefit. Other causes of traumatic cardiac arrest include obstructive shock (tension hemo/pneumothorax, pericardial tamponade), cardiac injury, and neurogenic shock (traumatic brain or cervical/high thoracic cord injury). Isolated chest compressions for obstructive shock have negligible effects unless the tension or tamponade is relieved and/or the cardiac injury is repaired or temporized.

Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) has been developed as a separate set of basic standards for managing traumatic injury. Part of the ATLS algorithm refers to the emergency resuscitative thoracotomy (RT). The majority of patients with thoracic trauma can be managed without operative intervention; however, a subset of patients (roughly 10%) may benefit from thoracotomy [1]. RT is often a controversial procedure that utilizes significant institutional resources and poses risk to both patients and providers in the form of iatrogenic injuries from needle sticks, open rib fractures, and infections. Given the nature of practicing emergency medicine within the community setting, consideration should also be given to the timely availability of a trauma or thoracic surgeon. Not having a surgeon immediately available for subsequent definitive care in your practice environment would be a contraindication to performing a RT.

The ATLS indications to perform RT include [2]:

- Relieve cardiac tamponade

- Repair cardiac injury

- Direct control of exsanguinating intrathoracic injury

- Cross clamp the aorta

- Open cardiac massage

- Remove air embolism

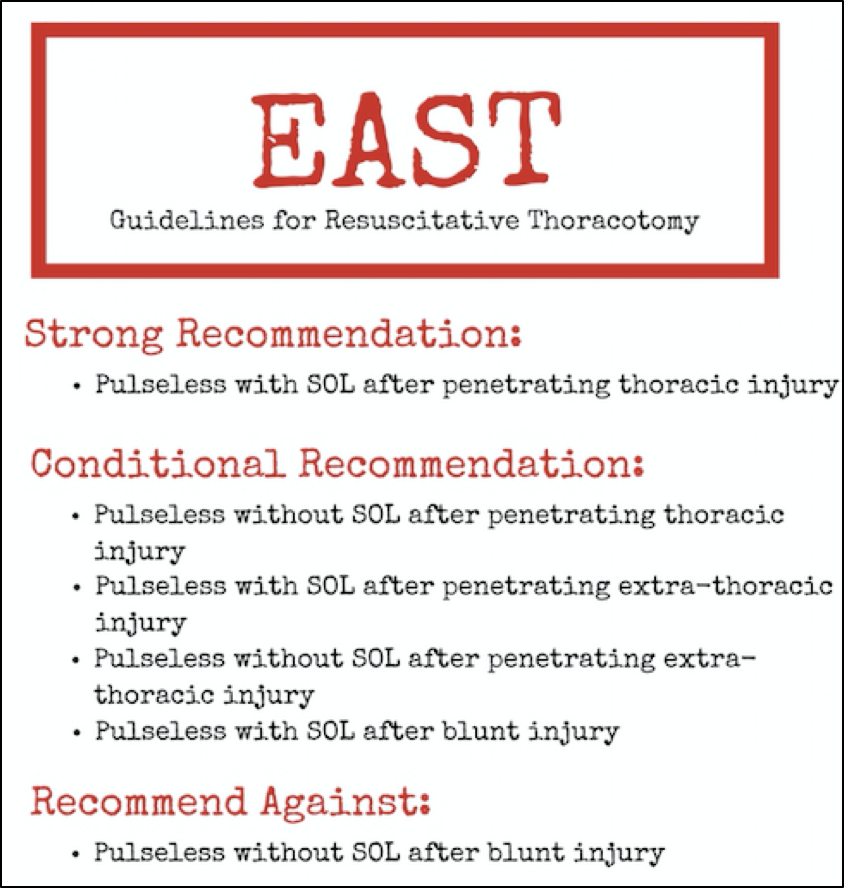

There have been multiple studies that have been conducted to identify which patients will benefit from RT. Current practice guidelines have been published by several organizations, including the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) and the Western Trauma Association (WTA).

The EAST guidelines published in 2015 focus on identifying candidates for RT based on mechanism of injury (i.e. blunt vs. penetrating) and the presence or absence of signs of life (SOL). SOL is defined as palpable pulses, measurable blood pressure, electrical cardiac activity, pupillary response, spontaneous breathing or purposeful movement of an extremity. The authors of the EAST guidelines sought to evaluate whether RT improved outcomes versus resuscitation without performing a thoracotomy. They performed a systematic review of the literature and identified 72 studies and 10,238 patients. They developed the above recommendations regarding performing RT [3]

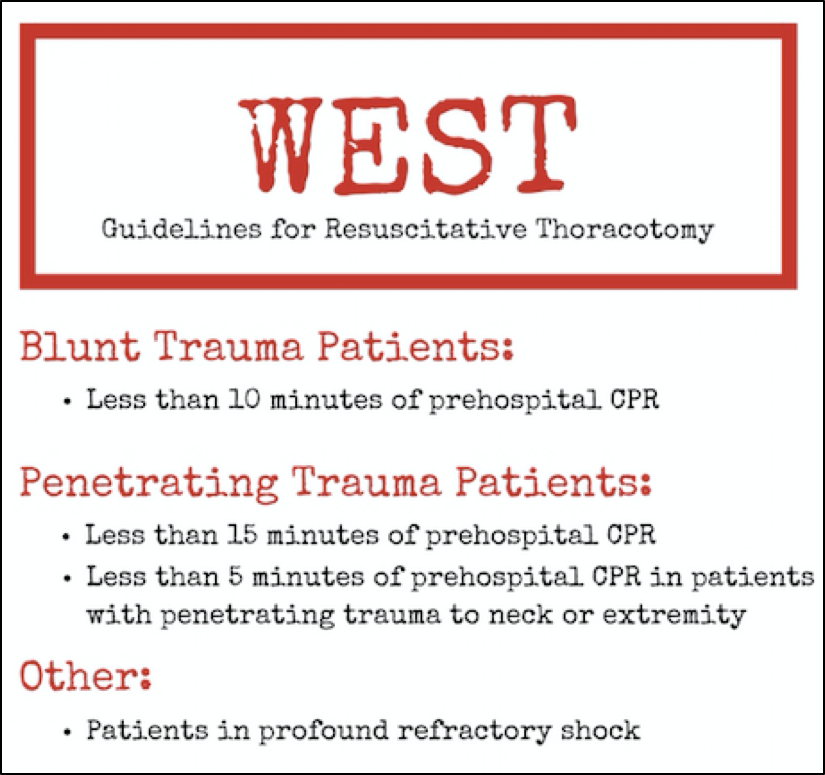

In contrast to the EAST guidelines which are based on the presence or absence of SOL, the guidelines put forth by the WTA (AKA the “WEST” guidelines) stratifies patients based on injury and transport time [4].

Additionally, a trauma and vascular surgeon in the UK named Dr. Karim Brohi, who also worked with the London Helicopter EMS (HEMS) system set up a website called Trauma.org to make trauma education resources publicly available worldwide. Trauma.org has also published recommendations on which patients are appropriate to receive RT.

Indications:

- Penetrating thoracic injury with unresponsive hypotension (BP <70) or arrest with previously witnessed cardiac activity.

- Blunt thoracic injury with unresponsive hypotension or rapid exsanguination from chest tube (>1500mL).

Relative Indications:

- Penetrating thoracic injury and arrest without previously witnessed cardiac activity.

- Penetrating non-thoracic injury or blunt thoracic injury and arrest with previously witnessed cardiac activity.

Who is most likely to benefit?

- Penetrating > Blunt trauma

- Thoracic > Extrathoracic

- Cardiac

- Stab wounds > GSW

- Thoracic > Extrathoracic

- Single injury > Multiple injury

- Less time since loss of pulses

- Previously witnessed cardiac activity

- Signs of life in the ED

Contraindications:

Just as there are multiple different recommended indications for RT, there are multiple different recommended contraindications:

- ATLS contraindications include no signs of life (SOL) on arrival, severe traumatic brain injury, or most likely extrathoracic cause of circulatory collapse.

- EAST guidelines recommend against RT in pulseless patients without SOL after blunt injury.

- Trauma.org uses blunt thoracic injury with no witnessed cardiac activity, multiple blunt trauma, or severe head injury.

Decision to perform emergency resuscitative thoracotomy

This decision can be difficult and is not taken lightly given the extremis of the patient, varying recommended indications and contraindications, extenuating circumstances, or preceding health/co-morbidities that may influence ischemic or reperfusion injury and recovery, resources in your area, and the risk to both patient and provider. Ultimately, this should be an individualized decision based on the patient in front of you, their likelihood of benefit, and your competence in performing the procedure.

Preparation

Prior to ever attempting this procedure on a patient, you should not only be familiar with the necessary steps and indications, but also with the tools available at your institution. Does your institution have a “thoracotomy kit” or individual tools that need to be gathered prior to patient arrival? Do you know where this is and how long it takes to get? Do you know how to set up the rib spreader appropriately? With a patient in front of you where seconds and minutes are critical, this should not be your first time touching the tools and you should not have to waste time looking up the procedure. Preparation is key.

Breathe. This is a high stress, high adrenaline procedure, with a risk of iatrogenic injury to the patient and provider. Make sure to put on a face shield and double glove. Ask for help if you need it.

Hold chest compressions: As discussed above, chest compressions do not accomplish much in traumatic arrests, interfere with rapid performance of RT, and increase the risk of iatrogenic injury to yourself as well as the provider performing chest compressions.

Procedure [5, 6]

- Quickly use betadine to prep the area.

- With the patient supine, raise their left arm superiorly exposing the axilla. You can consider taping their arm if needed.

- The patient is likely intubated, at which point you can stop positive pressure ventilation, or advance the ETT into the right main-stem to decompress the left lung making access to the heart easier.

- On the patient’s left, use a number 10 blade to cut inferior to the pectoralis major muscle above the rib in the 5th intercostal space (inframammary fold in a female patient), extending your incision to the anterior axillary line and curve superiorly in the direction of the ribs towards the axilla.

- Using a pair of scissors (i.e. curved mayos) dissect through the intercostal muscles to gain access to the thoracic cavity

- Insert the rib spreaders, positioning the crossbars towards the bed. This is important in the event you want to extend your thoracotomy to the right side (i.e. clamshell thoracotomy). If the rib spreaders are facing towards the sternum, you will have difficulty doing this.

- Spread the ribs wide, approximately 8 to 10 inches. The wider the better, as exposure is key.

- At any point, consider extending the incision to a clamshell thoracotomy if you need further exposure or if right sided injuries are expected. Duplicate the left sided incision on the right, likely using a second provider while you continue the next steps. Once right sided access is obtained, rib spreader can be moved to the center of the chest if needed.

- Once in the chest, grab a pair of small scissors and pick-ups. Push the lung out of the way. Locate the heart below the sternum.

- Make an incision in the pericardium. Be cognizant not to cut the phrenic nerve. To avoid this, make a vertical incision parallel to the phrenic nerve to access the pericardial sac, and bluntly spread the incision with your fingers. This will allow you to relieve tamponade and deliver the heart to assess cardiac activity and any penetrating cardiac injury.

- Some algorithms suggest stopping further resuscitation measures if no cardiac activity is seen at this point.

- If there is evident cardiac injury, apply direct pressure with your finger. Alternatively, a foley catheter can be placed in the wound and inflated with gentle traction applied.

- You can consider repair of the cardiac injury using 3-0 prolene with buttressed sutures. Make sure to avoid tying off a coronary vessel.

- Other obvious intrathoracic injuries with hemorrhage can be temporized with direct pressure, clamping, or 3-0 prolene sutures.

- Internal cardiac massage can be started immediately after relief of cardiac tamponade and/or repair of penetrating cardiac injury if the patient does not have a palpable pulse after this point. Make sure to use two hands with fingers together and extended to GENTLY squeeze the heart from apex to atria and avoid perforation of the thin walled right ventricle with your fingers.

- Defibrillate the heart using two small internal paddles, 15-30J, (if available) and if the patient has a shockable rhythm.

- Aortic cross clamping can be considered for exsanguinating injuries below the diaphragm. Avoid cross clamping the esophagus if possible.

- If you are able to revive the patient, get them to the OR as quickly as possible for definitive treatment.

Case Conclusion

In our young, healthy patient with single stab wound to the chest causing cardiac arrest of less than 5 minutes and signs of life at the scene, our patient is an optimal candidate for emergency resuscitative thoracotomy without any contraindications. While the rate of overall survival is low, our patient has the highest rate of survival based on his injury and his down-time. And while we cannot guarantee survival in this (or any) patient, his outcome cannot get any worse as he is currently pulseless. Since our institution has the necessary resources available and immediate access to trauma surgery, we decide to perform an emergency resuscitative thoracotomy in this patient.

Take home points

- Consider thoracotomy in your trauma patients with recent or impending loss of pulses.

- Thoracic trauma with refractory shock

- Pulseless with SOL (or previously witnessed cardiac activity) after any trauma

- Penetrating trauma without SOL and arrest <15 minutes

- Rapid exsanguination from chest tube

- Remember where your thoracotomy trays or tools are and know how to use the rib spreaders.

- Get the exposure that you need: Left anterolateral vs. Clamshell.

- Deliver the heart, control the bleed, and get the patient to the OR!

Written by Al Lulla, MD and Stephanie Charshafian, MD

Faculty reviewers: Chris Holthaus, M.D. (EM); Doug Schuerer, M.D. (Trauma Surgery)

References

- Hunt PA, Greaves I, Owens WA. Emergency thoracotomy in thoracic trauma-a review. Injury. 2006;37(1):1-19.

- Rhee PM, Acosta J, Bridgeman A, Wang D, Jordan M, Rich N. Survival after emergency department thoracotomy: review of published data from the past 25 years. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190(3):288-98.

- Seamon MJ, Haut ER, Van Arendonk K, et al. An evidence-based approach to patient selection for emergency department thoracotomy: A practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(1):159-73.

- Burlew CC, Moore EE, Moore FA, et al. Western Trauma Association critical decisions in trauma: resuscitative thoracotomy. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(6):1359-63.

- Weingart S. The Procedure of ED Thoracotomy. Emcrit. 2012. Available at: http://emcrit.org/podcasts/procedure-of-thoracotomy/. Accessed December 18, 2016.

- Inaba K, Spangler M. Trauma Surgeons Gone Wild: How to Crack the Chest. EM:RAP Podcast. 2016. Available at: https://www.emrap.org/episode/crackthe/traumasurgeons1. Accessed December 18, 2016.

- Trauma.org

- The ATLS Subcommittee, American College of Surgeons' Committee on Trauma, The International ATLS Working group. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2013; 74(5): 1363–1366

- Tan BK, Pothiawala S, Ong ME. Emergency thoracotomy: a review of its role in severe chest trauma. Minerva Chir. 2013;68(3):241-50.

- Kalina M, Teeple E, Fulda G. Are there still selected applications for resuscitative thoracotomy in the emergency department after blunt trauma? Del Med J. 2009; 81(5):195-8.

- Lorenz HP, Steinmetz B, Lieberman J, Schecoter WP, Macho JR. Emergency thoracotomy: survival correlates with physiologic status. J Trauma. 1992; 32(6):780-5

- Tyburski JG, Astra L, Wilson RF, et al. Factors affecting prognosis with penetrating wounds of the heart. J Trauma. 2000; 48:587-590.

- Boyd M, Vanek VW, Bourguet CC. Emergency room resuscitative thoracotomy: when is it indicated? J Trauma. 1992; 33: 714–721.

- Millham FH, Grindlinger GA. Survival determinants in patients undergoing emergency room thoracotomy for penetrating chest injury. J Trauma. 1993; 34: 332–336

- Morrison J, Poon H, Rasmussen T, Khan M, Midwinter M, Blackbourne L, Garner J. Resuscitative thoracotomy following wartime injury. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 2013; 74(3):825-29.

- Danne PD, Finelli F, Champion HR. Emergency bay thoracotomy. J Trauma. 1984; 24: 796–802.